For many people, autumn in Japan means only one thing - autumn foliage. Leaf viewing, or Kouyou, draws huge numbers to Kyoto year in year out, and many people spend long hours following the weather to choose the best day to go and see the leaves. Most people flock to Arashiyama, or one of the other popular spots such as Enrian temple or Eikando Zenrinji. However, for an equally, or even more beautiful experience, minus the crowds, you cannot go wrong with ‘The Temple of Flowers’.

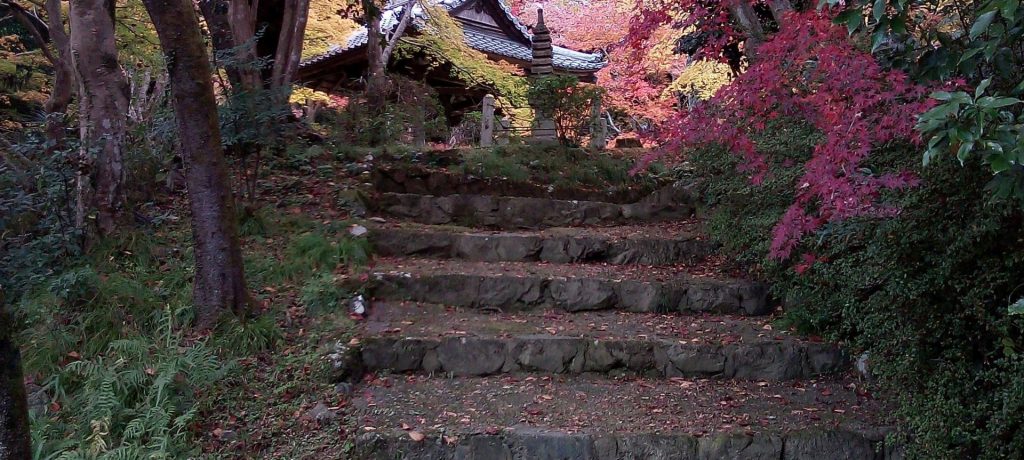

As with all the best places, Shoji-ji is at the top of a hill!

Located in the mountains on the outskirts of Nagaoka-kyo, Shoji-ji has over 100 maple trees and 100 cherry blossom trees within its grounds, earning and justifying its nickname, ‘The Temple of Flowers’. For a stunning sight, it is worth making the effort to visit this out of the way temple and to wander through its surprisingly large grounds. The trees were painstakingly arranged so that the cherry trees grew higher than the maples, allowing for better viewing in both of the tree’s respective seasons. Interestingly, the majority of the trees are clones, which are somewhat weaker than their naturally seeded cousins. Efforts are being made now to replace the clones with natural variations, but it is a time consuming process.

Beautiful colors can be seen in every season

While this temple guarantees beautiful sights, there is far more to it beneath the surface. Talking with the head monk revealed that while he appreciates the patronage of visitors during the autumn and spring, he wishes that they would take more interest in the temple and its history as well, rather than just the leaves, blossoms and instagram opportunities.

The temple has an interesting history, some of which sounds all too familiar, yet other parts reveal how power and status shifted during Japan’s turbulent past. Founded in 679, Shoji followed the unfortunate tradition of being destroyed by fire, thanks to the Onin Civil War which raged from 1467 to 1477 during the Muromachi period. There are believed to have been 49 buildings in the original precinct, which were far larger than today’s grounds. Along with the buildings, the temple records were also destroyed, so the exact details of the temple’s first 800 years or so are unknown.

What is known, is the power and status that the temple had upto and even after its destruction. It likely began as an imperial burial mound and grew from there. The site of the temple, Nagaoka-kyō (長岡京), was also the capital of Japan prior to Kyoto from 784 to 794, meaning that the temple would have been close to the centre of Japan’s power for a ten year period. Throughout its history, from those wishing to be buried there, to those who were seeking advice, Shoji was a place that attracted the elite of society. The big names of Hideyoshi and Tokugawa crop up here again and again, as do other famous families. It was actually a member of the Tokugawa family who rebuilt the temple after its destruction in the Onin War.

The power of the temple is also shown through its architecture, but in very subtle ways that are incredibly easy to miss.

They look like nothing, but the lines on the walls have an important message.

These five innocent, and slightly unappealing white lines actually declare the temple as being of such high status that is has a personal relationship with the emperor himself. (This is an architectural feature that is exclusive to buddhist temples.)

Aside from shoguns and emperors, one of the more famous people linked to the temple is Saigyo, a Japanese poet (1118-1190). He started his career as a ‘bushi’, an imperial bodyguard, but by the age of 22 he retired from public life to become a monk. He was particularly interested in the relationship between Buddhism and nature, and was naturally drawn to the beauty of Shoji-ji. One poem inspired by the trees in Shoji reads:

Which, reading between the lines, [roughly] translates to:

“For those who want to be alone and quiet, it is a sin of the cherry blossoms that they attract so many people to see them.”

In case you hadn’t already guessed, Saigyo was a hermit and liked to get away from the crowds. It is quite interesting that the head monk somewhat echoed Saigyo’s thousand year old words when he said he wished people would not just come for the beautiful flowers.

The beauty of nature is however prevalent within the temple’s architecture itself, making it slightly difficult to escape going for reasons other than beauty.

The cherry tree crests can be found everywhere here.

For example, cherry blossom marked ‘jimon’ (crests) cover the beautiful roofs, and the more modern glass windows act as mirrors, showing countless trees even when you have your back turned to them while praying. This even gives the impression that it is nature itself that you are addressing, rather than the temple’s buddha.

Reflections of nature seem to replace the buddha images

The fact that so many people ignore a temple’s buildings and religious aspects in favour of its natural beauty can somewhat be explained by the fact that Japanese temples, despite being religious buildings, do not exactly have a primarily religious function. Unlike other religious buildings such as churches and synagogues, Japanese temples were not made to be just places of worship. Their main function is actually to protect special or holy objects, which are commonly off limits to anyone who is not a monk. Thankfully Shoji’s treasures are open to the public, and include a large collection of statues from as early as 900AD. Unfortunately photography is banned, so I have nothing to show now, but the collection is incredible and includes a rare example of Tainaibutsu, a small buddha statue inside the ‘womb’ of a larger buddha statue. Other highlights include twelve deity statues in various poses with the signs of the zodiac incorporated into them.

With my Oiwa Jinja article still fresh in my mind, I expected this article to be about the increasing number of atheists in Japan and how that has turned temples into museums rather than religious buildings. But, what I actually discovered was that temples were always meant to be museums, designed to protect important cultural treasures. Surely shoji-ji’s treasures then are its trees? If so, the temple is doing a great job of preserving them for current and future generations.

Shoji is a great place for some quiet contemplation, and the beautiful trees are a fantastic sight to see, as are the other buildings in the temple grounds. Whether you go for the nature, history, philosophy or something else, there is much to be found.

As a bonus, Oharano jinja is very close and also has a beautiful garden and buildings to see. If you make the trip out here, seeing both places will make it even more worthwhile.

Oharano jinja, another beautiful temple located a few hundred metres from Shoji.

Harry Hammond is an Englishman lost in Kyoto, with a passion for history and architecture. He loves finding the hidden stories and history behind both the famous and the unknown buildings that shape this beautiful city.